The Morgan Affair And The First Third Party In American Politics

By Linda Speckhals | November 11, 2022

Some Of Morgan's Claims Were Questionable

William Morgan was born in 1774 and disappeared around 1826; the circumstances behind his disappearance are still shrouded in mystery. Because of his intent to reveal secrets of the fraternal organization, it was believed that he was kidnapped and killed by Masons. This stirred anti-Masonic sentiment and led to the formation of the first third party in the U.S.

Morgan’s background was a bit shady. He claimed to have served as a captain during the War of 1812, but is a bit dubious. He married in 1819; Lucinda Pendleton, his wife was more than 20 years younger. Two years later, he and his family moved to York, Upper Canada where he operated a brewery until a fire destroyed it. Impoverished, he returned to the U.S., first heading to Rochester, New York, and later Batavia where he worked as a bricklayer and stonecutter. According to local histories from the 19th century, he was a gambler and a heavy drinker, but his friends and supporters disputed this claim.

The Masons Didn't Approve Of His Character

Morgan claimed that while living in Canada, he became a Master Mason, although this is unsupported. It does seem that he attended a lodge in Rochester for a brief time, and he received the Royal Arch degree; to receive this degree, he had to receive the six degrees that precede it. He swore he had under oath, but this too was never proven. When he attempted to establish or visit lodges in Batavia, he was denied; members of the lodges disapproved of his character and thought his claims of being a Mason were a bit questionable.

His Publisher Also Had Issues With The Masons

When Morgan announced his intent to publish a book with the secrets of Masonic degree ceremonies David Cade Miller, a local newspaper publisher, gave him an advance. Miller had his own beef with the Masons, as he was said to have received the first degree (the apprentice degree), but lodge members in Batavia stopped him from advancing.

Morgan Was Kidnapped

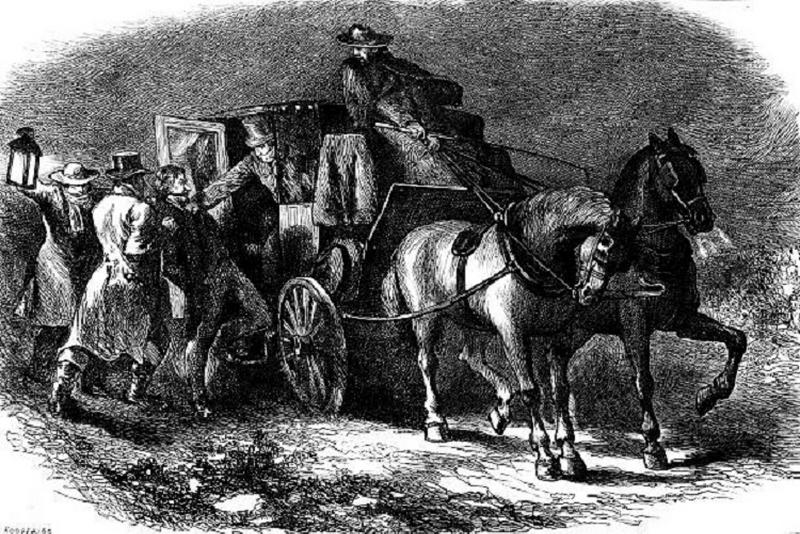

With the publication of the book, he broke the oath to not reveal the secrets of Masonry, and a few members of the Batavia lodge published a denouncement of Morgan. Someone also attempted to set fire to his house. He was then arrested for nonpayment of a loan and the alleged theft of a shirt and tie, and he landed in debtor’s prison, which would have made publication of his book more difficult. Miller paid Morgan’s debt and upon his release, Morgan was arrested again, charged with the failure failed to pay a two-dollar tavern bill. After some men convinced the jailer’s wife to release Morgan, they took him to a carriage which arrived at Fort Niagara two days later. After this, he was gone.

What Happened To Him Is Unclear

According to one account of the events that followed this, he was taken to the middle of the Niagara River and thrown overboard, presumably drowned. Henry L. Valance allegedly confessed on his deathbed in 1848 to participating in Morgan’s murder. However, this account was recorded in an anti-Masonic book by Reverend C.G. Finney, The Character, Claims, and Practical Workings of Freemasonry (1869). A group of Freemasons claimed they paid Morgan $500 to leave the U.S., and there were unverified sightings of Morgan in other countries. Several historians believe that the most credible explanation was that Morgan was killed by local Freemasons.

Morgan's Book Was Published

Although arrests were made in the case, the convicts didn’t serve much time. These included the county sheriff, Eli Bruce, who was a Mason, and three other Masons who had a role in the disappearance. Other Masons were tried and acquitted. Morgan’s disappearance didn’t stop the publication of his book, as Miller published it, and it became a bestseller, in part because of Morgan’s disappearance. Rumors about his fate abounded, and the governor of New York, DeWitt Clinton, who was himself a Mason, offered a $1,000 reward for information about Morgan’s whereabouts.

The Anti-Masonic Party Was A One-Issue Party

The Morgan Affair led to public outrage and protests against the Freemasons. While the Masonic officials repudiated the kidnappers’ actions, members of the organization remained under suspicion. Thurlow Weed, a New York politician, took advantage of the discontent, and brought opponents of President Andrew Jackson (who was a Mason) into the Anti-Masonic Party. They became the first party to hold a convention to nominate a presidential candidate, and they also became the first third-party. They ran William Wirt as its presidential candidate in 1832; he managed to receive Vermont’s seven electoral votes. The Anti-Masonic Party started to lose its relevance by 1835 though, in part because they had a very limited platform, and national attention shifted to other issues.

A Monument Was Erected To Morgan

A grave was discovered in a quarry near Pembroke, New York in June 1881. The artifacts in the grave suggest that this may have been Morgan’s grave, but some are suspicious of the timing of the discovery. They think it may have been to generate publicity for a monument to Morgan which was dedicated in 1882. This monument, erected by the National Christian Association, which was opposed to secret societies, reads in part that Morgan was “a martyr to the freedom of writing, printing and speaking the truth.”